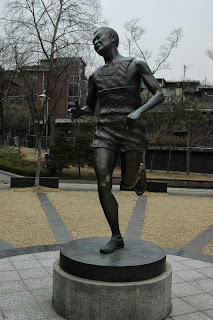

Sohn Kee-chung, and while he may not be well known in the west, his autobiography is part of the school syllabus in South Korea. He died in 2003, but his life is already part of the national mythology. You may not have seen it, but Sohn is the man at the centre of one of the iconic photographs of Olympic history.

On 9 August 1936, at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin. It shows three athletes on the podium during the medal ceremony of the Olympic marathon. At the back is the British silver medallist Ernie Harper. He is standing tall, shoulders back and head held high, a proud smile on his face. In front of him are two Korean runners, Sohn, gold medallist, and Nam Sung-yong, bronze medallist.

In the 1936 Olympics Games, Sohn's was just as defiant a victory. And if history has forgotten that, it is because it was many years before the wider world realised the significance of what he did. Between 1910 and 1948 Korea was part of the Japanese empire, who suppressed the indigenous culture and language. The flags that were raised and the anthem that was played to salute Sohn and Nam were not Korean, but Japanese, and the press and the IOC did not award or record the victory as a Korean triumph, but a Japanese one. Sohn was not even allowed to compete under his own name, but went by the Japanese transliteration, Son Kitei.

During his stay in Berlin Sohn tried to tell the would that they should not think of him as Japanese. He would sign his name in Korean characters, and would often draw a small picture of his country alongside his autograph. After the race he tried to tell the newspapermen again and again that he was Korean, not Japanese, but his minders refused to translate his remarks. Montague's mistake was repeated right around the world, with one conspicuous exception.

Back in Korea the newspapers blurred the Japanese flag out of the photographs of Sohn. The Korean daily Dong-A Ilbo, which still exists today, carried the photo – with the Japanese flag scratched out – on its front page on 25 August. Immediately afterwards the Japanese government shut the Dong-A Ilbo down for nine months and arrested, then tortured, eight of its journalists.

Early Life

Sohn was born in Sinuiju, in what is now North Korea, in 1914, four years after the country was annexed by Japan. In school he was taught Japanese, and had to learn his own language in secret. He began to run, racing against friends on bicycles, and when his teachers realised how talented he was they sent him to study in Seoul. There he was coached by Lee Sun-il, who used to make him run with stones strapped to his back and his pockets filled with sand to help him build his strength and stamina.

Beginning lives as a runner

The regime worked well. When he was 17, Sohn won his first marathon. And in the next five years, between 1931 and 1936, he would run in 12 more, winning nine of them. In November 1935 he ran the Tokyo marathon in 2hr 26min and 42sec, a world best, five minutes faster than the time that won Argentina's Juan Carlos Zabala gold at the 1932 Olympics.

The next year Sohn finished third in the Olympic trial, behind his countryman Nam. The Japanese had made a lot of noise about how they intended to finish third in the medal table. They were happy to send the three Koreans to Berlin, a 12-day train journey away, to represent them in the marathon, so long as they ran under Japanese names and in the Japanese kit.

Zabala was the favourite for the race itself. He led the field out from the Olympic Stadium, the 56 runners trailing in his wake through the Grunewald forest. His fast pace meant he stretched out ahead of the pack. Sohn, 90 seconds behind after three miles, considered making a move to catch him. But as he set off he heard a voice come over his shoulder. It was Harper, the Englishman. "Take it easy," he said, "let Zabala run himself out." Sohn couldn't speak English, but he understood the sentiment. For the next 14 miles he and Harper ran together. And then, after 19 miles, the exhausted Zabala tripped and fell. Sohn and Harper passed him. Staggering and stumbling, Zabala dropped out two miles later.

Harper began to suffer with blisters, and his shoes filled with blood. Montague wrote afterwards that "Harper's performance, the last 10 minutes of it with a blistered and bandaged foot, can vie with Owens' sprinting as the finest performance of the Games." Sohn kicked on, racked with pain, his leaden legs pounding the tarmac track. "The human body can do so much," Sohn said later. "Then your heart and spirit must take over."

Heart and spirit carried him up one final slope, back into the stadium and across the line. As athletes always do, Sohn looked up at the scoreboard as he finished. He did not see his name, but the Japanese transliteration of it, and alongside it was not his nationality, but that of his nation's conquerors.

Conflict with the Japanese coloniser

Soon after the race the Japanese athletes held a party to celebrate Sohn's victory. But neither he nor his team-mates were there. Instead they were at the house of An Bong-geun, a prominent member of the Korean nationalist movement. At An's house Sohn is said to have seen the Korean flag, forbidden from use, for the first time in his life. He was overcome with shame at the memory of being forced to wear the Japanese Rising Sun emblem in Berlin.

Serve as a National Marathon Coach

After the war, Sohn became the head coach of the Korean marathon team. Fourteen years on from Berlin, after Korea had been liberated from Japan and then occupied by the US and the Soviet Union, Sohn led a team of South Korean runners – the first athletes ever to wear the Korean flag on their kit – to a clean sweep in the 1950 Boston marathon. He was still coaching 42 years later, and was in the stadium in Barcelona to watch his protege, Hwang Young-jo, win South Korea's second Olympic gold in the marathon.

In his own country Sohn was already a hero. But it took 50 years for the rest of the world to acknowledge what he had done. He was an instrumental member of the Seoul Olympics Organising Committee, and it was only when Korea was awarded the Games that the athletics community rewrote the record books. In 1986 Sohn was invited to a ceremony in Culver City in California, where his nationality and name were changed on a monument to Olympic marathon winners.

Two years later he carried the torch into the stadium for the opening ceremony of the 1988 Olympics, to a standing ovation from 80,000 of his countrymen.

"The Japanese could stop our musicians from playing our songs. They could stop our singers and silence our speakers," Sohn said before he died. "But they could not stop me from running."

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment